The Woodlands Township Elections November 2022

Subsidence in The Woodlands

Authored by Robert H. Leilich, President, The Woodlands MUD 1, with contributions from Laura Norton, Director Montgomery County MUD 47, Bob Rehak, ReduceFlooding.com, Dr. Neil Gaynor, President, Montgomery County MUD6. This paper does not necessarily represent the positions or opinions of the agencies that the authors serve and are expressly those of the authors as private citizens.

BACKGROUND

In recent years, considerable controversy has emerged about increasing groundwater pumping, involving the rights of property owners to the water under their land versus public concern that too much drawdown is causing subsidence, contributing to increased flooding and the altering of drainage patterns.

On January 5, 2022, Groundwater Management Area 14 (GMA 14) unanimously approved revised groundwater pumping conditions, known as Desired Future Conditions (DFC). The revised DFC stated: “In each county in Groundwater Management Area 14, no less than 70% median available drawdown remaining in 2080 or no more than an average of 1.0 additional foot of subsidence between 2009 and 2080 is allowed.”

The Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District’s (LSGCD) General Manager, Samantha Reiter, stated, “It allows the [conservation districts] to do what they want in their counties how they see fit, based on the best available science.” In the same newspaper article, John Martin, general manager of Southeast Texas Groundwater Control District, said the draft report would be finalized at a Feb. 23 GMA-14 meeting.[1] A final report is due to be submitted on March 5, 2022.

The proposed DFC was developed with the aid of computer modeling using the Houston Area Groundwater Model (HAGM) and adjusting the pumping distribution in each county starting with the distribution used in the 2016 round of joint planning in GMA 14.[2] Dr. Neil Gaynor independently reviewed this Phase 1 Subsidence report[3] presented by LSGCD and questions the validity of inputs to the HAGM model, especially those related to compaction, as they greatly influence the validity of its outputs. He also questions how the 1.0 feet of average additional subsidence was calculated.[4] In another paper, Gaynor notes, “… the costs to be borne by some residents and governmental entities in The Woodlands should no longer be treated as simple externalities. It should be possible to optimize surface water and groundwater sources to meet future consumer demand, but not at the cost of further damage to property and infrastructure.”[5]

Roughly 80 percent of the groundwater pumped in Montgomery County comes from the Jasper aquifer. Present models do not do a good job of modeling compaction in the Jasper aquifer, compared to emerging measurements that show that compaction exists.[6] LSGCD tacitly admits that the accuracy of compaction modeling of the Jasper needs more work, especially since the Jasper aquifer is a major source of water for Conroe, SJRA, and other large volume water producers.

Houston Advanced Research Center’s (HARC) Science Advisory Committee (SAC) recommended the installation of at least twenty new continuous GPS stations co-located or closely spaced with Jasper Aquifer groundwater wells and regular water level monitoring. Within three years, residents and decision-makers would have new insights into ongoing subsidence. This methodology will commence a proper assessment of subsidence risks, if any, and help guide any remediation actions.[7]

The US Geological Survey is developing a new model, called the GULF-2023 groundwater flow model. This model, once accepted by the Texas Water Development Board and Houston-Galveston Subsidence District, will replace the current Houston Area Groundwater Model (HAGM). Residents and governmental entities in the northern part of the Gulf Coast Aquifer System have a clear stake in the reliability of the GULF-2023 model.[8]

The primary concern of the authors of this paper are the words “no more than an average of 1.0 additional foot of subsidence between 2009 and 2080 is allowed.” The expression “1.0 additional foot of subsidence” is meaningless for three reasons:

- Impossibility of accurately determining an average

- It ignores the seriousness where subsidence greatly increases the risk of flooding, especially where subsidence has already contributed to major damages.

- Subsidence lags aquifer drawdown

Mike Turco, General Manager of the Houston-Galveston subsidence District said that the constraint—one foot of subsidence on average across the county in the next 50 years—could mean some areas could experience up to 3 feet. He further stated that, “The concern is now with the deregulation, ... [efforts to slow subsidence have] been undone.”[9]

With climate change and development that is not offset by mitigation measures, our concern is that the harm caused by subsidence will greatly outweigh the financial benefits of increased groundwater pumping (which is less expensive compared to surface water). Subsidence is irreversible, increases flooding risks, and changes drainage patterns. Further, subsidence (soil compaction) causes a reduction in soil permeability (water absorption) which is also permanent and contributes to flooding.

The largest urban area in the United States affected by land subsidence is the greater Houston, Texas, metropolitan region. Notwithstanding widespread petroleum production, most of the subsidence is caused by groundwater withdrawal.[10]

OBJECTIVES

Our objectives are simple and straightforward:

- No increase in groundwater pumping allowances until there is sufficiently strong evidence establishing groundwater pumping levels that will not lead to further subsidence.

- Increase the use of surface water to meet demand and require all Groundwater Reduction Program (GRP) participants to honor their contracts

History in Harris County showed that when large volume water producers acted independently, public interest was not served. It is estimated that Montgomery County will need 300,000-acre feet per year (afpy) of water by 2070 and Lake Conroe can only produce 100,000 afpy.[11] To develop the future water supplies for our area to meet our County's demands, we need to work toward regional partnerships. Effective regional partnerships, that promote the public interest, should champion GRPs that provide opportunities for large as well as smaller water providers to utilize surface water resources. The authors of this paper, however, see considerable animosity between LSGCD and SJRA, as evidenced by lawsuits and inability to work out solutions that are not hostile to public interests.

LEGAL

Generally, Texas groundwater belongs to the landowner. Groundwater pumping historically was governed by the 1904 Court Doctrine, called the Rule of Capture, which grants landowners the unrestricted right to capture the water beneath their property, regardless of the effects of that pumping on neighboring wells, and by inference, other side effects.[12]

For many years since 1904, the courts have generally upheld this doctrine. The relationship between groundwater pumping and subsidence was unknown at the time, plus population, water demand, and groundwater pumping have increased exponentially since the law was passed.

Though the Doctrine remains unchanged, the more recent Texas Water Code, Section 36.108 now states a DFC must consider 9 factors, specifically:

(1) aquifer uses or conditions within the management area, including conditions that differ substantially from one geographic area to another;

(2) the water supply needs and water management strategies included in the state water plan;

(3) hydrological conditions, including for each aquifer in the management area the total estimated recoverable storage as provided by the executive administrator, and the average annual recharge, inflows, and discharge;

(4) other environmental impacts, including impacts on spring flow and other interactions between groundwater and surface water;

(5) the impact on subsidence;

(6) socioeconomic impacts reasonably expected to occur;

(7) the impact on the interests and rights in private property, including ownership and the rights of management area landowners and their lessees and assigns in groundwater as recognized under Section 36.002;

(8) the feasibility of achieving the desired future condition; and

(9) any other information relevant to the specific desired future conditions.

(d-1) After considering and documenting the factors described by Subsection (d) and other relevant scientific and hydrogeological data, the districts may establish different desired future conditions for:

(1) each aquifer, subdivision of an aquifer, or geologic strata located in whole or in part within the boundaries of the management area; or

(2) each geographic area overlying an aquifer in whole or in part or subdivision of an aquifer within the boundaries of the management area.

(d-2) The desired future conditions proposed under Subsection (d) must provide a balance between the highest practicable level of groundwater production and the conservation, preservation, protection, recharging, and prevention of waste of groundwater and control of subsidence in the management area.[13]

While the above is a step in the right direction, we believe the Code is not specific enough with regard to subsidence, especially the vagueness of the fifth factor, “impact on subsidence.” It needs to be tightened in accordance with the objectives stated above. The authors of this paper are fully aware that LSGCD directors do not agree with our assessments, drawn from the many studies that have been conducted and our own, physical observations.

Groundwater Conservation Districts have the legal right to limit groundwater pumping to do no public harm. When they refuse to do so, they are ignoring their public responsibility.

SURFACE WATER VS GROUNDWATER

Most large cities get all or most of the water supply from lakes, rivers, reservoirs, or other surface water sources. About 70 percent of the freshwater used in the United States in 2015 came from surface water sources. The other 30 percent came from groundwater.[14]

Texas is one of the largest users of surface water. The size of the state and its agricultural, industry, and population base are responsible for its large water demand.

Montgomery County, however, is a major groundwater user within the state. Starting in 2016, the appointed directors of the LSGCD mandated a reduction in groundwater pumping to 64,000 acre-feet of water per year, well below the 80,000 acre-feet that was being pumped out of the ground at that time. To comply with this mandate, the SJRA created a Groundwater Reduction Plan, that was subscribed to by over 130 large volume water producers, representing over 80 percent of the water used in Montgomery County.[15] This partnership led to the building of a surface water treatment plant to process water from Lake Conroe. Since the election of new LSGCD directors in November 2018, replacing appointed directors, this GRP partnership has begun to fracture, creating friction between those that want to pump more groundwater and those that could suffer if subsidence is permitted to continue. The real issue is not the depletion of groundwater, but the degree to which it causes or contributes to subsidence, the consequences which vary greatly throughout the county.

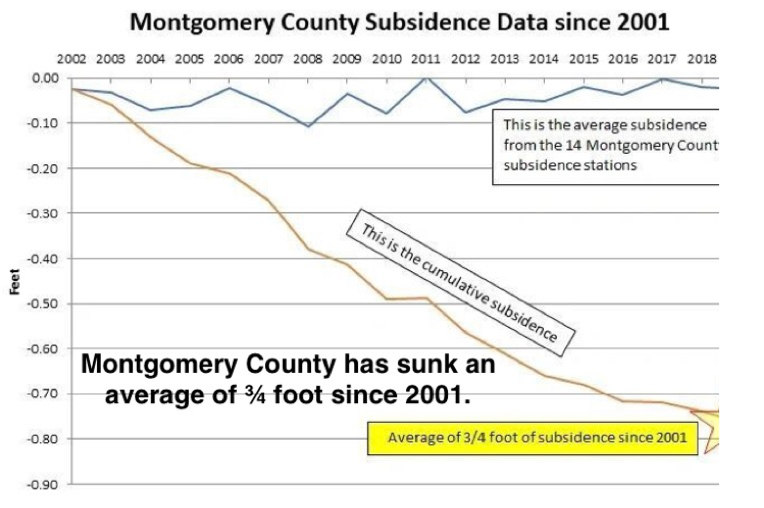

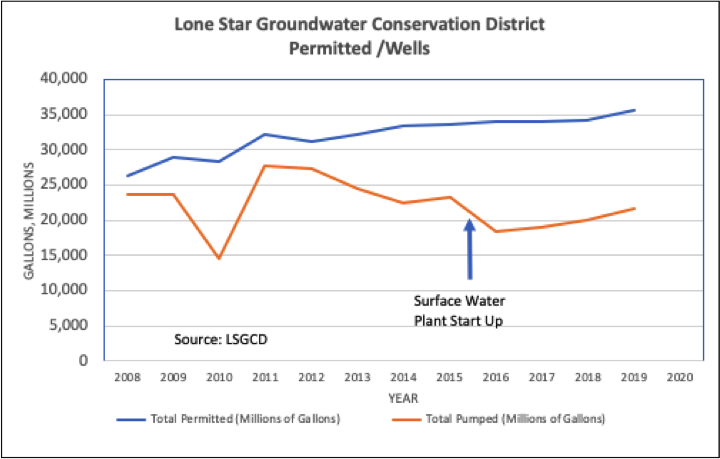

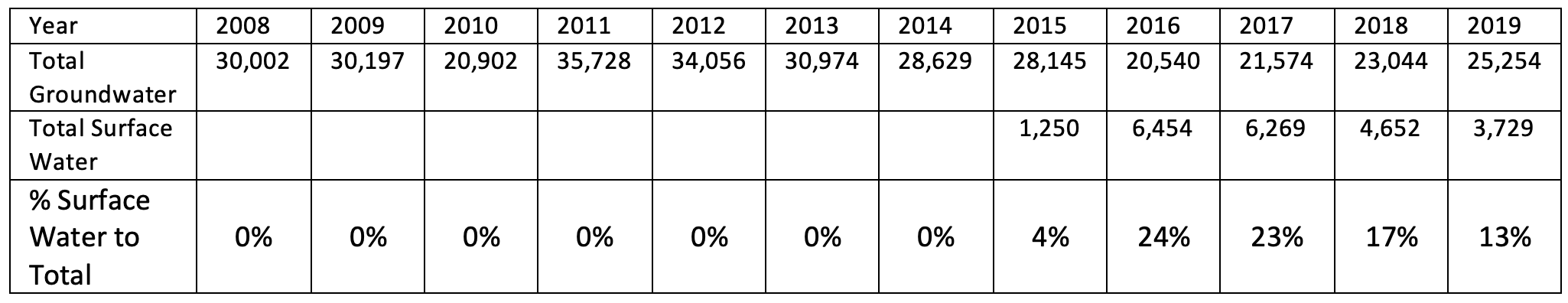

Until 2015, virtually 100 percent of commercially produced water for all uses in Montgomery County was from groundwater. The following two charts show water production among permitted wells within the LSGCD and water production by the SJRA since 2015.

The percentage of surface water to total water produced is:

Compared to the approximate 70 percent US average of using surface water for domestic consumption, surface water consumption in Montgomery County hovers around 20 percent in recent years, even excluding the significant amount of groundwater withdrawn from thousands of private wells in Montgomery County.

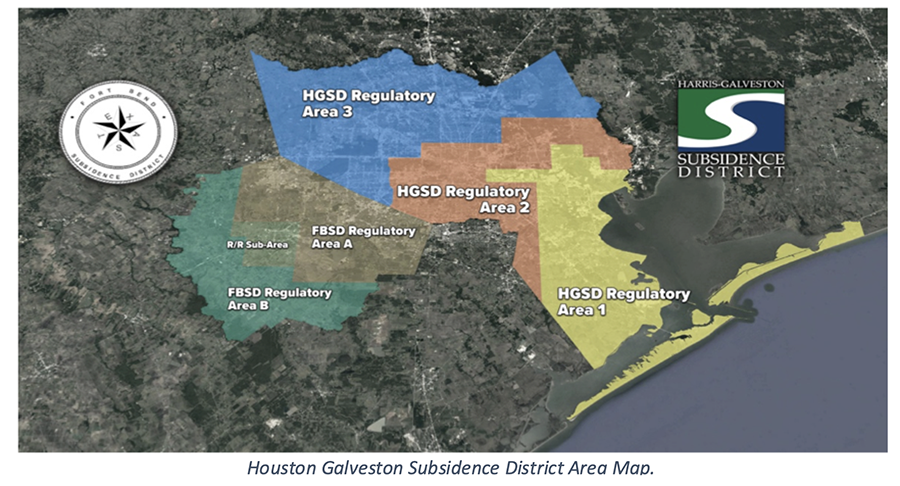

Groundwater withdrawal in Harris and Galveston counties is regulated by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (HGSD), a special purpose district created by the Texas Legislature in 1975 for the purpose of reducing land subsidence.

The HGSD requires all water suppliers in Harris and Galveston counties to reduce groundwater pumping based on the rate of subsidence in their area. In the HGSD regulatory areas map shown, areas 1 and 2 have already converted to surface water. Area 3 requires conversion to alternate water via a 30% reduction of groundwater usage by 2010, 60% by 2025, and 80% by 2035.[16]

Due to the inelastic nature of sediments – in particular the clays – in areas where subsidence occurs, the subsidence is permanent. Flooding resulting from subsidence in the Harris / Galveston area has resulted in major losses of land and property over the past 50 plus years. Houston and much of Harris County has experienced up to 6 feet in this period.[17] As an extreme example, the Baytown subdivision of Brownwood, east of Houston along the Ship Chanel, experienced nine feet of subsidence due to excessive groundwater pumping. The entire community had to be abandoned

The HGSD maintains a network of eight subsidence monitoring stations to continually measure subsidence. Minor subsidence of approximately 0.5 foot has been measured at monitoring stations located in the southern portion of the District.[18]

In Montgomery County, up to three feet of subsidence has occurred between 1906 and 2000. Montgomery County does not have a Subsidence District. Though subsidence issues are included in the LSGCD’s responsibilities, it appears to be of relatively low priority. Its present elected directors all were heavily funded by contributions from a large private utility with major interest in increasing groundwater pumping.

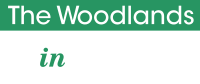

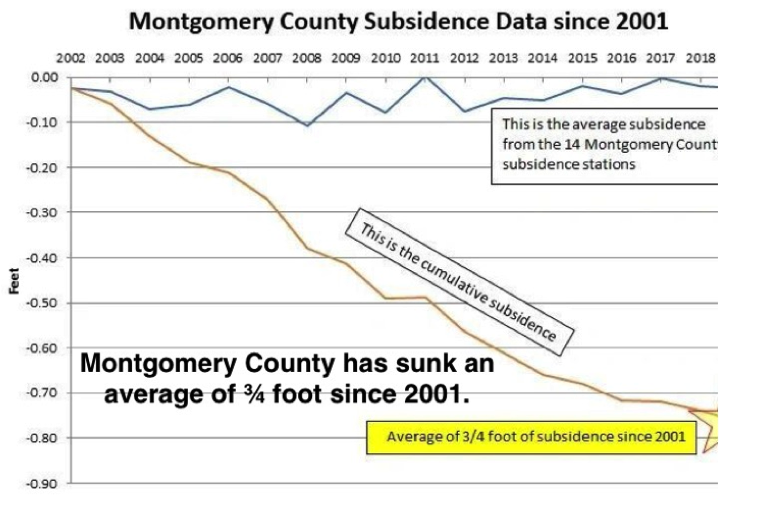

Though not specific by measurement site in Montgomery County, the following Chart shows average subsidence since 2001.[19]

This chart, prepared from HAGM data has a caveat noted by LSCGD; “The average drawdown represents a calculation using all active model cells for the Jasper in Montgomery County. The maximum compaction location can vary within Montgomery County depending upon which model cell shows the largest amount of compaction. The results presented are from the HAGM and must interpreted within the model’s limitations.”[20]

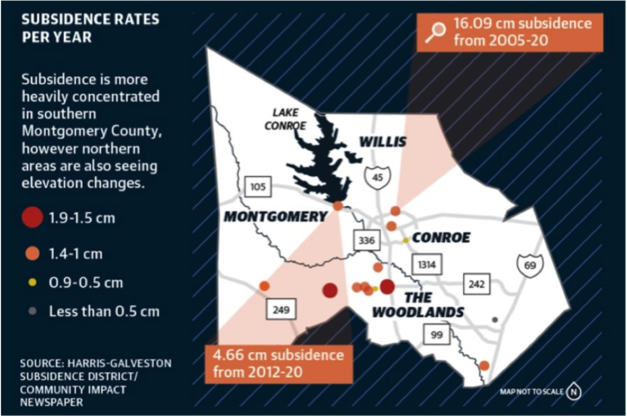

Published in the Community Impact Newspaper on February 24, 2021, the following chart shows another depiction of subsidence in Montgomery County. [21]

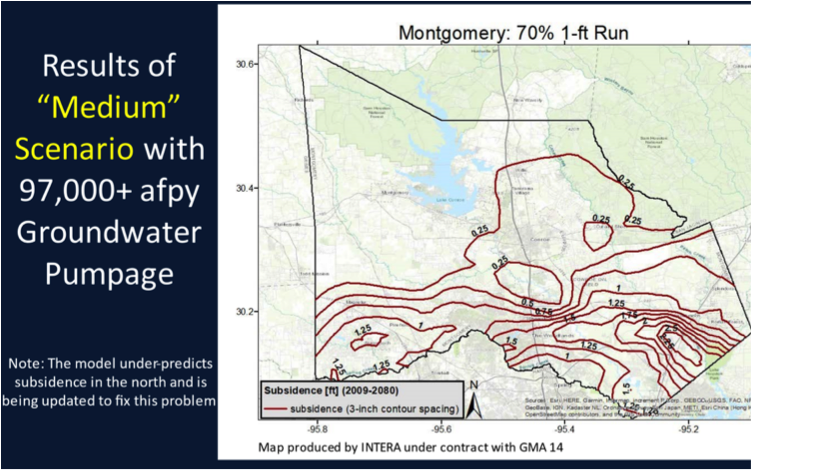

In an October 2020 presentation by the SJRA, titled “Groundwater Management Update,” the consulting firm, INTERA, released the following chart showing potential subsidence rates under the proposed DFC’s recommended by GMA 14. We believe that this is unacceptable.

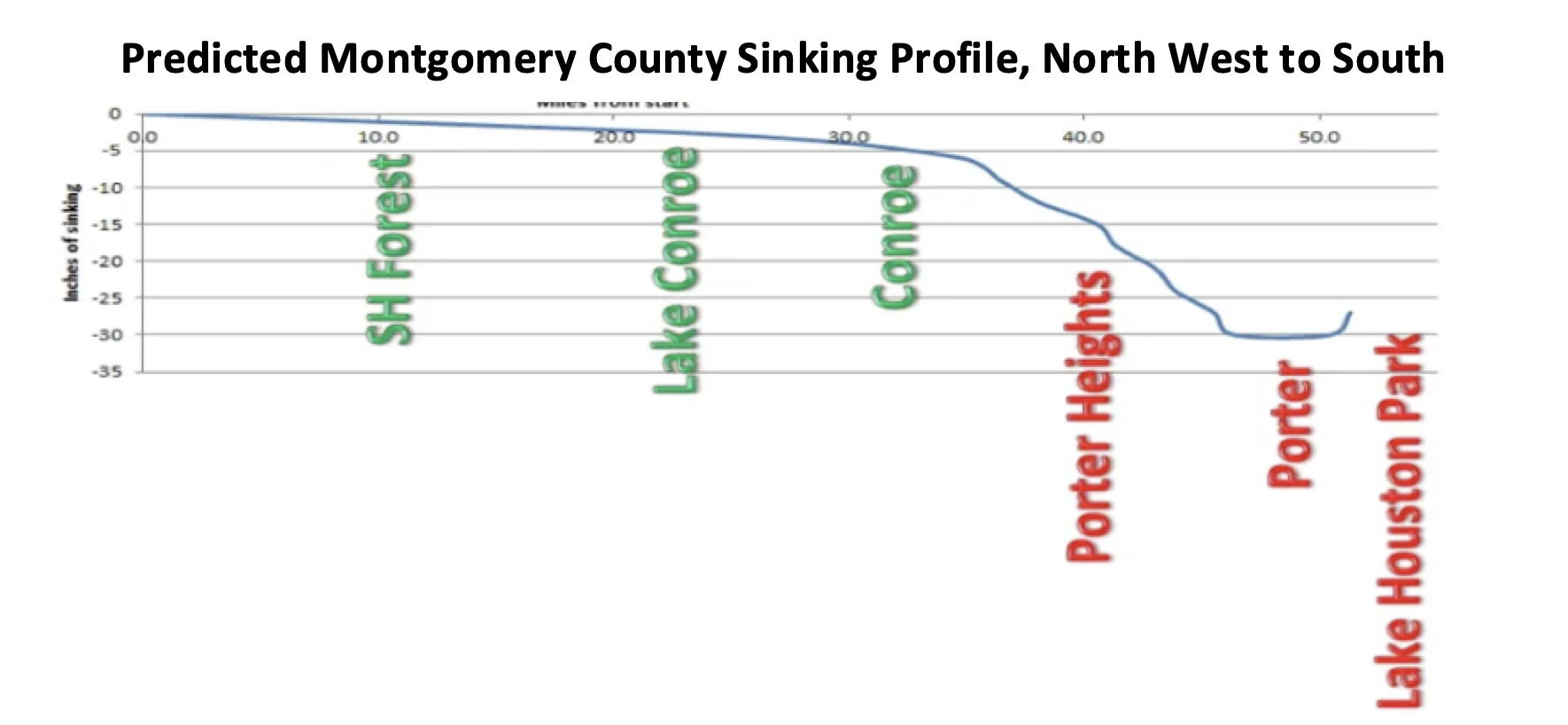

Two grassroots organizations, one called Stop Our Sinking (www.stopoursinking.com), and the other, Reduce Flooding (www.reducefloodimg.com) have put together a wealth of additional information about subsidence and is a good complement to this paper. A particular chart put together by this group is as follows.

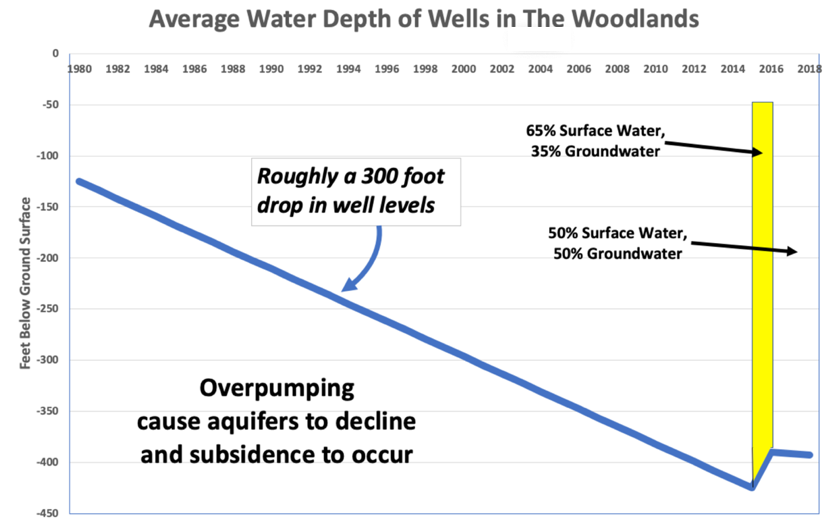

Reducing water well levels appears to be the major cause of subsidence in Montgomery County. In 2015, the San Jacinto River Authority (SJRA) completed a nearly $500 million water treatment plant and infrastructure to use surface water. The original goal was to use a blend of 65 percent surface water and 35 percent groundwater. The following graph, summarized from SJRA’s well level data dramatically shows that well levels rose when groundwater pumping was reduced to 35 percent of consumption.

In recent years, non-participation in the Groundwater Reduction Plan (GRP) agreement by some agencies and private utilities led to loss of income by SJRA and the need to substitute more groundwater for surface water to avoid unfairly burdening remaining participants in the GRP with major rate increases. Even with a revised goal of going to a 50/50 mix, well water levels have continued to decline, albeit more slowly.

Declining aquifer (well) levels also introduce other problems:

- Disturbances in fault lines

- Damage to well casings

- Higher groundwater pumping costs (greater pumping heights and bigger motors)

- Need to drill wells deeper or totally replace them

- Permanent loss of aquifer capacity due to soil compaction

- Higher water rates for surface water users

Laura Norton, Director of MUD 47 researched three fault lines in The Woodlands and homes that have been damaged by subsidence. As an example, Mark Meinrath, whose home is on Bentgrass Place in The Woodlands, was featured in a recent Houston Chronicle article. In the article, he noted that the front part of his brick home, built in 1992, fell about a half inch a year. Some relief (slowing the rate of subsidence) came, when surface water use began in 2015. As the SJRA reduced its surface water production in response to some private utilities and government agencies abrogating their GRP payments, Meinrath said that his house began sinking more rapidly again.

LSGCD’s position on subsidence was best expressed by its President, Harry Hardman, who said that the property rights of a few individuals cannot be the basis for groundwater decisions for the entire county. He further stated, “The people, in The Woodlands have to weigh what is more important to them: Having a higher water bill and not having subsidence or … a reasonable amount of subsidence [and] keeping your water bills more affordable.”[22]

Marvin Jones, an attorney for the private utility Quadvest, wrote in a letter that “attempting to throttle groundwater production in Montgomery County to prevent subsidence in The Woodlands is misguided at best.”[23] This utility stands to financially benefit from increased groundwater pumping.

ADDITIONAL SOURCES OF INFORMATION

This paper barely touches on information about subsidence and flooding in the Houston Metropolitan Area and Montgomery County in particular. Besides references in the footnotes, the following is a list of some additional resources and information:

Houston Advanced Research Center: https://harcresearch.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=abfb3d1bdbb04954a66afb0f661fc535

Texas Water Development Board: https://www.twdb.texas.gov/groundwater/models/research/subsidence/subsidence.asp

Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District: https://www.lonestargcd.org/strategic-study

Harris-Galveston Subsidence District: https://hgsubsidence.org/science-research/

Unites States Geological Survey: https://txpub.usgs.gov/houston_subsidence/

Texas Water Development Board: https://www.twdb.texas.gov/groundwater/models/research/subsidence/subsidence.asp

Texas A&M University: https://agrilifetoday.tamu.edu/2021/02/04/sinking-situation-of-subsidence-in-houston-gulf-coast/

Springer Open: https://geoenvironmental-disasters.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40677-021-00199-7

LEGISLATIVE RELIEF NEEDED

The GMA 14 is expected to grant approval for a 50 percent increase in groundwater pumping through its new DFC allowance. While groundwater pumping may not necessarily increase right away, it paves the way for increased pumping in the future unless the Texas Legislature or Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) take steps to quell the inevitable increase in groundwater pumping and subsidence.

We recognize that there are two sides of this issue: Large Volume Users of groundwater who are vocal in their position that subsidence is a minor issue, that it may affect but a small number of property owners, and the largely silent public. Decisions regarding future increased groundwater pumping should be deferred until more GPS measuring sites and extensometers are in place, observations of groundwater pumping and subsidence are made, and better models are proven to be reliable.

Legislative help is needed to stop irreversible subsidence in Montgomery County, and perhaps other Texas counties as well. With Southeast Texas facing the potential of future flooding and spending billions of dollars on flood mitigation, it does not appear that lessons have been learned about the relationship between groundwater pumping and subsidence. Our specific recommendations for legislative action are:

- Suspend implementation of a revised DFC for Montgomery until the Phase 2 Subsidence Study is completed and the accuracy of the Gulf-2023 model to model subsidence in the Jasper aquifer is verified.

- Require additional GPS devices be installed at key locations in Montgomery County, including at least one extensometer in the Jasper aquifer as part of the Gulf 2023 model verification.

- Modify the Texas Water Code to explicitly not permit subsidence in areas subject to flooding.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS AND CONTRIBUTORS

Bob Leilich is President of The Woodlands MUD 1 and served previously as President and Trustee of former MUD 2. He is an original member of The Township Drainage Task Force (now One Water Task Force), and was the initiator of the current study to control flooding by Spring Creek. He has witnessed the devastation of flooding among family members, in the subdivision where he lives, and helping some residents recover from flood damage. He has spoken or provided testimony at the Texas Water Development Board, Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District, and Groundwater Management Area 14. He has degrees in Mechanical Engineering and Industrial Management. He was a professional consultant for 40 years before his retirement in 2010.

Laura Norton developed and maintains the website StopOurSinking.com. She is a member of One Water Task Force, a director of MUD 47 and previous appointee to the Woodlands Water Trustee Board. Laura has spoken or testified at the TWDB, LSGCD, GMA 14, SJRA, SJRA-GRP and SJRFPG. Laura has appeared on MCPLive.TV in an interview about subsidence and has hosted many fault tours for elected officials in the region. Laura is a retired Certified Public Accountant.

Robert Rehak, began hosting www.ReduceFlooding.com as a pro bono effort after Hurricane Harvey to create a single repository of information related to flood issues in the Lake Houston area and to maintain public awareness of and interest in flood mitigation. Before retiring, he spent 45 years as an executive in marketing and communication working with many Fortune 500 companies. He has BS and MS degrees in Journalism and has produced many publications and is widely recognized for his public services.

Neil Gaynor is President of Montgomery County Municipal Utility District No. 6, a member of the San Jacinto Regional Flood Planning Group, representing the Upper Watershed, a Board member of the Grogan’s Mill Village Association, and a member of The Woodlands One Water Task Force. He is a retired geologist, with a Ph.D. in geosciences from UT-Dallas and has 40 years of experience in oil and gas research, exploration, and development in the U.S. and internationally. Neil’s community activities include developing a watershed protection plan with the Spring Creek Watershed Partnership. He has a deep interest in equitable water resource management and flood mitigation.

[1] https://communityimpact.com/houston/pearland-friendswood/environment/2022/01/05/houston-area-groundwater-conditions-approved-at-gma-14-meeting/

[3]https://www.dropbox.com/s/dkg33o1an1797l4/SUBSIDENCE%20INVESTIGATIONS%20Phase%201%20Report_Final%20%2009012020.pdf?dl=0

[4] Dr. Neil Gaynor, “Subsidence Investigations - Phase 1 Assessment of Past and Current Investigations, August 6, 2020. Sent to the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District. Unpublished

[5] Dr. Neil Gaynor, “Subsidence, Fault Activation and Groundwater Production in The Woodlands,”

[7] Ibid.

[9] https://communityimpact.com/houston/conroe-montgomery/environment/2021/02/24/as-ground-sinks-debate-ensues-over-montgomery-countys-groundwater/ Community Impact News, February 24, 2022

[10] Holzer, T.L., & Galloway, D.L., (2005). Impacts of land subsidence caused by withdrawal of underground fluids in the United States, in Ethenl, J., Haneberg, W.C., and Larson, R.A., eds., Humans as geologic agents, Boulder, Colorado, Geological Society of America Reviews in Engineering Geology, XVI, p 87-99, doi:10.1130/2005.4016(08)

[11] https://www.twdb.texas.gov/groundwater/docs/GCD/lsgcd/lsgcd_mgmt_plan2020.pdf page 23, Table 4.

[14] https://www.usgs.gov/special-topics/water-science-school/science/surface-water-use-united-states

[17] Houston Galveston Flood Control District

[18] 2016 LSGCD Annual Report. The time frame of this observation is not mentioned.

[20]https://www.dropbox.com/s/dkg33o1an1797l4/SUBSIDENCE%20INVESTIGATIONS%20Phase%201%20Report_Final%20%2009012020.pdf?dl=0 LSGCD Phase I Subsidence Investigations, Appendix A, no page given.

[21] https://communityimpact.com/houston/conroe-montgomery/environment/2021/02/24/as-ground-sinks-debate-ensues-over-montgomery-countys-groundwater/?fbclid=IwAR2QOjqmVQN32ykclS_FDfTD5mh-8AvtYUjkfBa5O36Q4JzTqiPWzhE_2Vk

[22] Community Impact Newspaper, May 12, 2021. https://communityimpact.com/houston/the-woodlands/government/2021/05/12/district-outlines-long-term-water-management-goals-in-montgomery-county/

[23] Houston Chronicle. 4/19/21 and The Woodlands Villager. 4/28/21. “Water war raging around area as new regional goals on table.” https://www.pressreader.com/usa/houston-chronicle/20210419/281621013169131