The Woodlands Township Elections November 2022

Escalating Water Battles in Montgomery County and the 2022 LSGCD Director Elections

The ongoing legal battles between the San Jacinto River Authority (SJRA), the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District (LSGCD), the Cities of Conroe and Magnolia, the private water utility Quadvest, and others became more vocal as a result of a series of recent interviews by MCPLive.TV, Hank’s Think Tank podcast, and a Water Forum held at New Caney’s Randall Reed Stadium on September 20, 2022, sponsored by Hank’s Think Tank and Quadvest.

An important election is coming up this November for four of the seven seats on the LSGCD Board of Directors. Voters should inform themselves of the issues, as this affects everyone in Montgomery County. Our precious groundwater resource should be managed on a conservative basis for widespread public benefit. It should not be treated as an inexhaustible resource.

There are two contested LSGCD Board seats in the November, 2022 election, Position 3 and Position 7. Two candidates for the Board are independent and not supported by private utilities. They both have my support:

James Ridgway, Jr., (Pos. 3), has four years of experience as a MUD Director and is an investigative journalist who has researched water issues in Montgomery County.

John Yoars, (Pos. 7), a process and chemical engineer, is a top-notch water expert.

Many water experts in The Woodlands are endorsing John and James.

WATER ISSUES

Here is some background about why the fight occurred. The main issues are water supply (and costs), subsidence (flooding), and legal property rights.

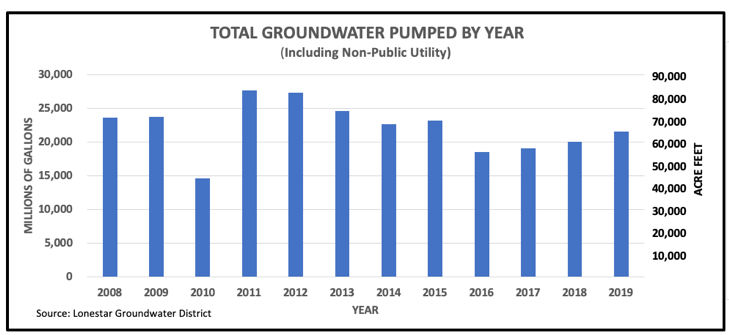

Groundwater pumpage data, published in the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District (LSGCD) annual reports between 2008 and 2019, is as follows, shown in millions of gallons and in acre-feet[1].

With the production of surface water, beginning in the second half of 2015, the reduction in groundwater pumping was significant, but soon started to inch upward again in 2017 due to lower surface water production and increases in total water demand (largely due to population growth).

It is clear and well established[2] that pumping water out of the ground in excess of recharge rates causes:

- Reductions in well water levels

- Increased pumping costs (bigger motors, more electricity)

- Collapsed water well casings

- Aquifer declines

- Soil compaction and reduced capacity for aquifer storage

- Land subsidence, increasing frequency and severity of flooding

- Disruption of irrigation ditches

- Damage to foundations of commercial and residential real estate

- Damage to public infrastructure such as roads and bridges

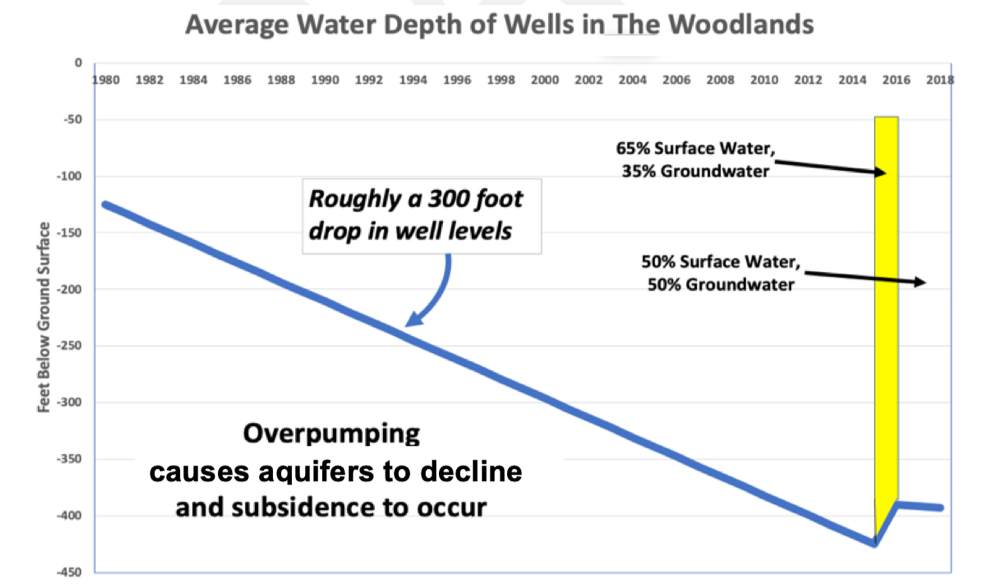

An undisputed fact is that we cannot continue to pump groundwater at unsustainable rates. It is not clear what the sustainable rate is, but there may be some good clues, beginning when SJRA started using surface water. The simplified graph shown here[3] illustrates the changes experienced in well level declines, at least in The Woodlands, since 1990.

|

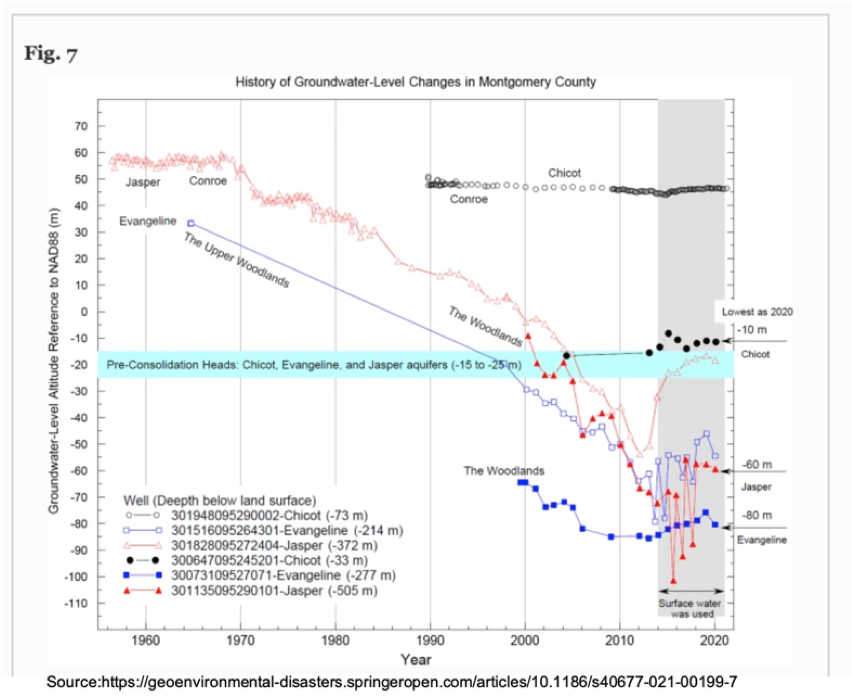

The graph below summarizes aquifer declines in Montgomery County, according to the authors shown in the source URL link.

|

SUBSIDENCE ISSUES

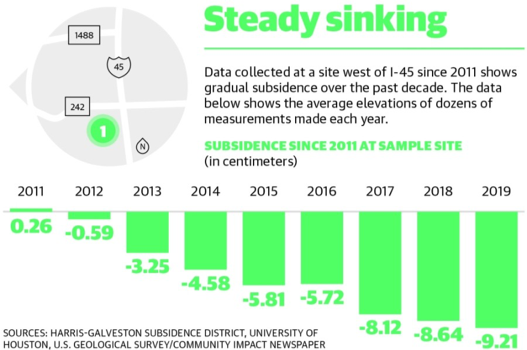

The rate of subsidence varies according to many factors, including the amount of recharge deficit, the aquifer where the withdrawals are made, and the characteristics of the soil. According to the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (HGSD), subsidence in The Woodlands, at least at the collection site, was as shown in the adjacent chart. At the subsidence measuring site known as PAM-13, near Bear Branch Park in The Woodlands, subsidence since 2000 amounted to about 9.25 centimeters, or about 3.6 inches.

The rate of subsidence varies according to many factors, including the amount of recharge deficit, the aquifer where the withdrawals are made, and the characteristics of the soil. According to the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (HGSD), subsidence in The Woodlands, at least at the collection site, was as shown in the adjacent chart. At the subsidence measuring site known as PAM-13, near Bear Branch Park in The Woodlands, subsidence since 2000 amounted to about 9.25 centimeters, or about 3.6 inches.

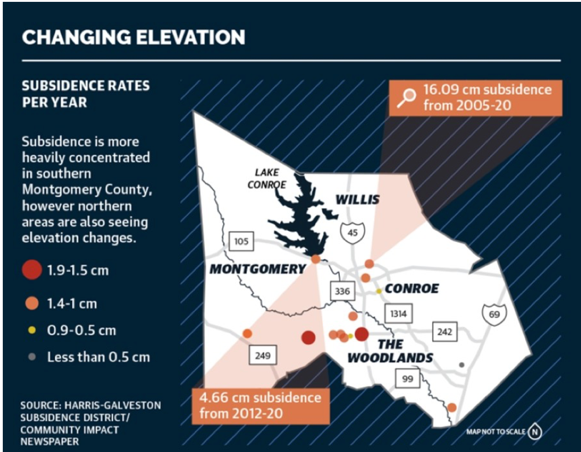

The adjacent chart shows the “hotspots” where the most significant incidence of subsidence is occurring in Montgomery County. It is ironic that the very site of the Water Forum in New Caney on September 20 was near, or part of, one of the most susceptible areas for subsidence.

The adjacent chart shows the “hotspots” where the most significant incidence of subsidence is occurring in Montgomery County. It is ironic that the very site of the Water Forum in New Caney on September 20 was near, or part of, one of the most susceptible areas for subsidence.

Current data appears to suggest that long-term subsidence in Montgomery County will continue at groundwater withdrawal rates greater than roughly 50,000 to 70,000 acre-feet per year.

Many people feel that the LSGCD does not adequately acknowledge the seriousness of excessive groundwater pumping and subsidence, claiming “we don’t know the exact correlation between subsidence and groundwater pumping.”[4] Even then, LSGCD is willing to accept a county-wide average of one foot of subsidence over the next forty-plus years. That average, of course, will not be uniform. Any more subsidence, period, is unacceptable to people living in low lying areas, especially along Spring Creek, that have already suffered one to three feet of subsidence since 2000 and who have experienced flooding solely due to this subsidence. These areas remain far more susceptible to more than “average” subsidence. There is an old adage that, “A man can drown wading across a river that averages six inches deep.”

LEGAL PROPERTY RIGHTS (LSGCD vs SJRA)

Generally, Texas groundwater belongs to the landowner. Groundwater pumping historically was governed by the 1904 Court Doctrine, called the Rule of Capture, which grants landowners the unrestricted right to capture the water beneath their property, regardless of the effects of that pumping on neighboring wells, and by inference, other side effects.[5]

For many years since 1904, the courts have generally upheld this doctrine. The relationship between groundwater pumping and subsidence was unknown at the time, plus population, water demand, and groundwater pumping have increased exponentially since the doctrine was established.

In 1995, last amended in 2017, Chapter 36 was added to the Texas Water Code, governing the responsibilities of Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs). It said that GCDs, in one of nine conditions, had to consider the “impact on subsidence.” Unfortunately, the law is not more specific, granting considerable leeway in its interpretation.

In 2001, stakeholders within Montgomery County got together to address the growing concerns of water supply and declining well levels. It was widely recognized that this was a regional problem and not a local problem related to only more heavily populated areas like The Woodlands and Conroe. There was virtual consensus that a regional solution was needed. The Texas legislature responded by creating the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District, whose initial mission was to study the aquifers and determine how best to address the county’s groundwater problems. In 2006, the District adopted its initial rules regulating the amount of groundwater that could be pumped by utilities in the county.

In response to the District’s rules, SJRA proposed a regional solution that any utility in the county could choose to join. The proposal, called a joint Groundwater Reduction plan, was implemented in 2010 with about 80 participants deciding to join. The cooperative, regional approach offered by SJRA was considered the best, lowest-cost solution for the foreseeable future, calling for the construction of a surface water plant and a distribution system at a cost of around $550 million. Many argue that the GRP was forced or coerced due to the potential of a $10,000 daily fine from Lone Star for not complying and that it should have been put to a public vote. Some now claim that the GRP is illegal and unenforceable, the heart of the dispute between SJRA and a handful of the participants in the contract. Further, some argue that they derive zero benefit from paying GRP fees since they do not receive any surface water. At risk is the potential of SJRA’s GRP Division defaulting on bond payments to the Texas Water Development Board.

Irrespective of whether it was voluntary or forced, the GRP was designed to minimize costs by distributing surface water to the largest consumption (population) users closest to the surface water treatment plant. Using the surface water in this way made more groundwater available to those not geographically positioned to easily use surface water. It would have been prohibitively expensive and wasteful to try to provide every GRP participant with a share of surface water simply to say “we are getting what we paid for.”

With the replacement of an appointed LSGCD board with an elected one in 2018, all of whom received financial support funded by the private water utility Quadvest[6], the relationship between LSGCD and SJRA changed from amicable to adversarial, centering on GRP contracts. Though the LSGCD and Quadvest claim that those opposed to these contracts have won every legal battle so far (which is not an accurate statement), these victories are largely on procedural matters, as the legality and enforceability of GRP contracts has yet to be decided.

In addition to shedding GRP contracts, another high priority of Quadvest (and LSGCD’s sympathetic Board of Directors) is preserving the rights of property owners to water under their property in accordance with the 1904 Rule of Capture even if it comes at the sacrifice of the property rights of those being subjected to additional flooding due to subsidence.

WATER FOR THE FUTURE

The fact remains that at some point we have no choice and must use surface water to extend the life of our groundwater wells and meet growing demand. The claim that we have virtually unlimited groundwater available without doing harm is simply not supported by the evidence of declining well levels, aquifer levels, and subsidence. We don’t want to find ourselves in the position of many Louisiana farmers whose wells are running dry[7].

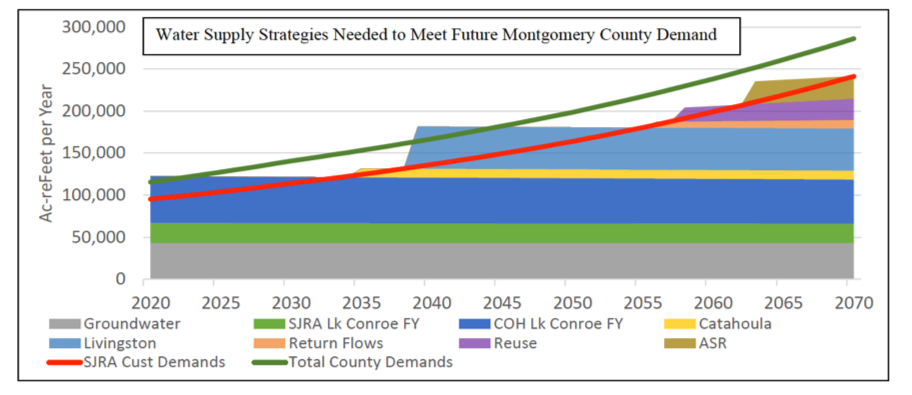

The graph below is a summary of the estimated growth in water demand for Montgomery County[8]. It suggests, as early as 2030 or so, that we are going to need even more water than existing levels of groundwater pumping and maximum capacity of the surface water plant can provide.

|

The GRP is a community (regional) solution to a common need for water and future supplies of water. Many believe that everyone in Montgomery County needs to pay for additional resources, as everyone benefits, directly or indirectly, by adding water resources that do not involve groundwater. As an example of community benefits, thousands of people pay considerable taxes to the Lone Star College District, the Conroe Independent School District, and the fire department who have never, ever, gotten anything directly in return. Think how each of these organizations could have survived, if everyone who never derived any direct benefit from these entities stopped paying taxes that support them. It would be chaos and display a selfish and complete lack of community. Similar to GRP fees, these taxes are not voluntary and are punishable if you fail to pay. Many people who don’t use transit but pay taxes to subsidize transit riders benefit by these people not adding more cars to heavily travelled commuter corridors.

Supplying water to people in Montgomery County is no different.

In a guest editorial in the Golden Hammer, published in March 9, 2021, Simon Sequiera president of Quadvest said, “… consumers in Montgomery County who are supplied entirely by groundwater are subsidizing the water bills of the folks in The Woodlands, who receive the blend. That’s been true since the inception of this scheme. So, if The Woodlands residents now have to pay increased water bills to keep their houses from potentially flooding, so be it.”

Jim Stinson, General Manager of The Woodlands Water Agency said, “The new LSGCD rules (permitting higher pumping allowances) place Montgomery County in the crosshairs of a critical decision on the future of groundwater: Should groundwater be managed on a regional basis that has widespread public benefits? Or is groundwater a private property commodity where everyone, including individual landowners and for-profit water companies, have pumping rights that adversely impact others?”

The public needs to have a say in this fight. The election of four (out of seven) LSGCD board members this November will speak for public involvement.

There is growing support for two candidates, James Ridgway, Jr., and John Yoars, whom I support and who are not receiving financial and public support directly or indirectly from Quadvest.

Since the outcome will affect everyone in Montgomery County, everyone should study the qualifications, voting records, independence, and objectivity of those running related to groundwater pumping and subsidence. We can make a difference.

[1] An acre-foot is the equivalent of an acre of water, one foot deep, equal to 325,851 gallons

[2] USGS 2019

[3] SJRA Static Groundwater Well Levels 1980 – 2018 (of six wells)

[4] Quote from Jim Spigener, a Director of LSGCD on Billy Graff’s, MCPLive.TV “Water Show,” recorded at https://youtu.be/o3vEE69gwNw

[6] Quadvest and three other utilities contributed more than $90,000 to the Restore Affordable Water Political Action Committee. Nearly $30,000 additional Quadvest funding went into Megaphone. Also tens of thousands in funding came from the owners of the Woodlands Oaks Utility, a realty company, and Crystal Springs Water Company.